What is needed for a more circular construction sector? Insights from Sien Cornillie, Circularity expert at NAV

NAV, or "Netwerk Architecten Vlaanderen," is a professional organisation for architects in Flanders. It offers various services including professional development and advocacy for the architectural sector. NAV also fosters networking opportunities and provides advice on legal, technical, and management aspects. The network is currently working on a position paper on circularity. We sat down with Sien Cornillie, an expert on circularity and energy at NAV. This interview reflects her own opinion.

Sien, can you tell us more about your work at NAV?

I have been working at NAV’s research department since April 2023, where I serve as an advisor on circularity. My responsibilities include developing training programs, writing knowledge articles, working on research projects, guiding a working group on circular construction, and contributing to NAV’s position paper on circularity and the role of the architect. Before this, I worked as an architect at various architectural firms. At NAV, our research department consists of six members, each with their own specialization.

Circularity is a crucial topic in the construction sector. What do you consider the main principles of circular architecture?

Circularity is a term that few architects use, but the underlying design principles are not new. Vernacular architecture, for example, can be considered as “circular building” avant-la-lettre, with the usage of local resources and building methods to create a pleasant living environment, in consideration for local climatic conditions, are its core make-up.

In principle, this translates to a design mindset that works with what is available. It’s about how we can create comfort for humans within planetary boundaries using the knowledge and resources we have today. Unfortunately, the market has gone overboard with endless opportunities on what’s available on the market, and our notion of comfort has become hopelessly skewed.

Although this philosophy, which starts from locality, is increasingly being adopted by designers, it is difficult to implement true circularity broadly in the construction sector. It requires a reconsideration of our current economic growth model, which desperately tries to reconcile the idea of virtual infinity with a physically finite supply of resources and planetary biocapacity.

How do you see this shift applied to the construction sector?

At the core of conscientious consumption lies a fundamental economic and cultural shift. We need to think differently and validate differently. The societal and monetary value of knowledge about repair, reuse, and transforming existing buildings must take precedence over producing or consuming more or different materials. In the construction sector, economically viable service models must emerge for advising against building, building less, or primarily reusing, which contradicts the prevailing expectations. We prefer to hear that we can still consume, just differently. The idea that we need to drastically reduce consumption at least in certain areas, to ‘save the climate’ is a difficult message.

We often look to the government to set an example and introduce certain stimuli or regulations. Unfortunately, many policy choices hinder true circularity. The obligation and long-term subsidization of energetic renovations, for example, overlook the environmental impact of the toxic but affordable materials typically used. Additionally, government-developed LCA tools that assess a building’s impact over its entire lifecycle do not account for the CO2 impact generated outside national borders. This maintains the competitive advantage of ‘made in China’ over locally grown building products, these are simply no sustainable policy choices.

The construction sector would benefit from socially just policies that allow for experimentation and provide space for small consumers, processors, and producers. A circular construction sector requires us to think globally and act locally.

What are the biggest challenges for the construction sector in embracing sustainable practices and circularity?

The societal shift towards a circular economy is a significant part of this. To reduce waste,we need to approach construction projects more like an ecosystem, in which the many small parts impact the larger whole. That's a complex (not to be confused with “complicated”!) puzzle, but therein lies just the key: if we embrace this complexity and organize accordingly, that's already part of the answer.

This requires extensive specialization, expertise, and a willingness to collaborate intensively from all construction partners, as well as a shift in roles and responsibilities within the value chain. The importance of this knowledge and the time needed to consolidate it, must also be more highly valued.

Architects will increasingly need to integrate themselves as one of the links in the collaboration chain, where they have so far held the direction and final responsibility due to their monopoly. The profession will hopefully diversify much more in the near future to support this need for specialization, but essentially, the repertoire of crucial design questions and material knowledge of every architect can still undergo a significant transformation. The core task of the architect, to ensure socially justifiable projects, remains unchanged - in my opinion.

Finally, I see many architects doing fantastic (thinking) work, but much knowledge is lost in separate projects. Knowledge consolidation is a major challenge, even within offices. We must continuously discover and share findings about what works and what doesn’t. NAV wants to take a responsibility in this challenge as well.

What role does technology play in sustainability challenges within the construction sector?

Technology can certainly contribute to sustainability goals, but it is not a catch-all solution. It still depends on how, when, and in what application we use (new) technologies. Smart buildings are a good example. Smart technology aims to achieve an ideal comfort level, but what does that mean exactly? And is it the same for you and me? Technology is useful if it helps us, in the absence of a “no- or low-tech” solution, to effectively reduce energy consumption.

What are some inspiring examples from the sector?

In Flanders, I admire initiatives like the Recupcentrale Gent and the Materialenbank Leuven, doers like Hitch and Onbetaalbaar, public players like the cities of Mechelen and Sint-Niklaas, small contractors like the Huismus and Woonder, developers like Whitewood, and thinkers and connectors like Labland and Endeavour – to name just a few.

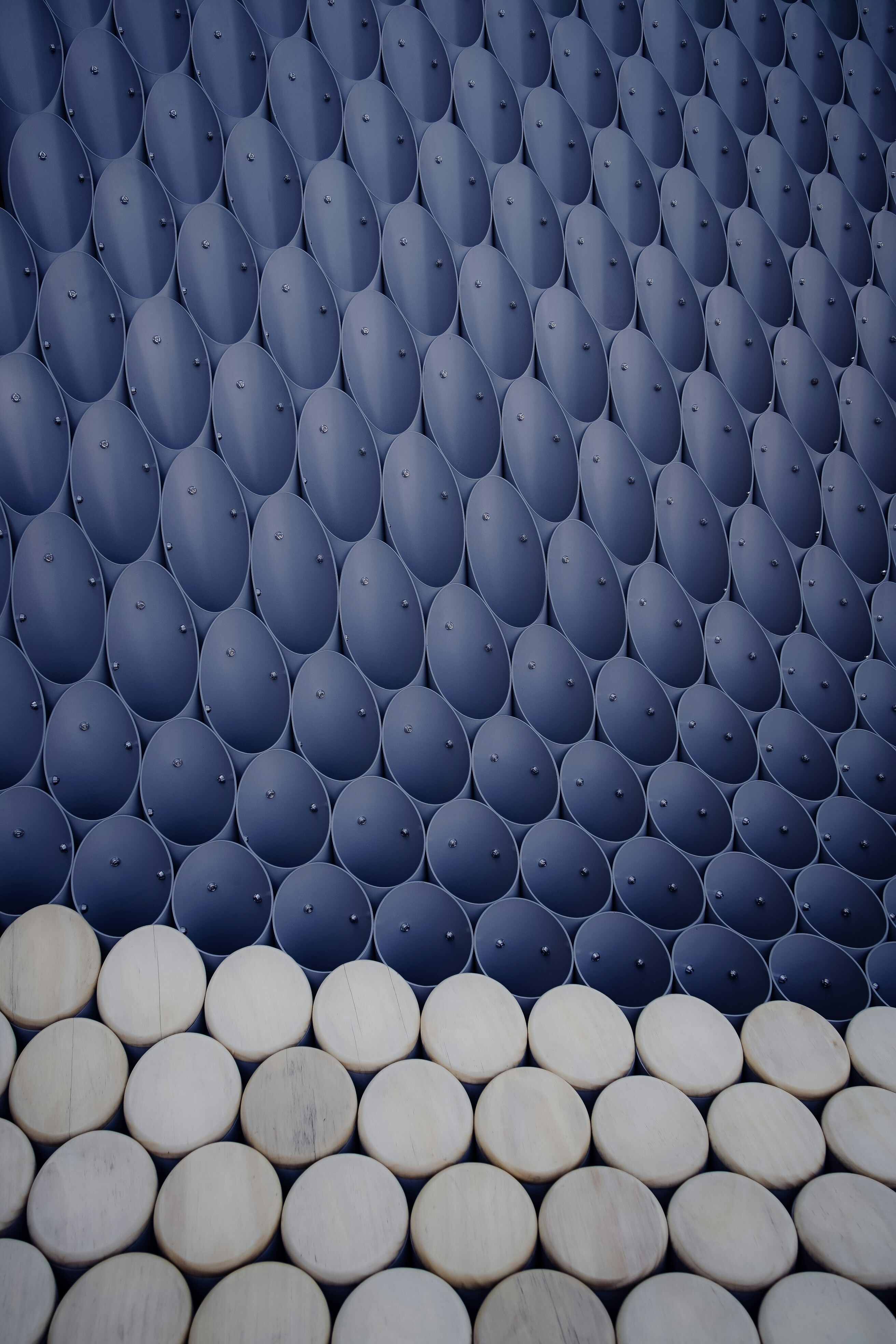

Among architects, there are more and more who prioritize sustainability as the basis for architectural quality and, from there, sharpen the debate and dare to experiment with varying success. I think of DVVT architects, who have managed to spark international aesthetic appreciation for the, in retrospect very circular, principle of “rough construction as finished construction” (with the right materialization that is). I also think of Bureau bouwtechnieken, who dare to explore less-traveled paths in technical design. I think of Rotor, who have been hammering on the same nail for years as an architectural firm and now mainly acts as researchers and material brokers: we need to reuse more. Kudos also to BC Architects, who developed a production branch to create new building products from clay and waste streams, and to RE-ST, who are carrying out the principle of not building on small and large scales, as well as firms like NU Architectuuratelier, Marge architects, and a2o, who introduce a refreshing culture of collaboration within the sector.

I have not mentioned many others, so I especially want to emphasize that I have great respect for all construction professionals and clients who, in this unfavorable economic context, continue to prioritize the climate to the best of their ability.

How can we as individuals make a difference?

Everyone can contribute to a more circular society. Inform yourself, formulate concrete ambitions, dare to ask difficult questions to construction partners, and be open to unorthodox solutions. Also, question your own comfort: do I need this space? And does this space need to be heated? Don’t be swayed by sales pitches and pretty words, but consider what is truly sustainable, climate adaptive and environmentally friendly. Is a ‘circular’ product made from recycled materials from China really the best solution? And know that there is a lot of knowledge and information available. For example, the government has developed a guide to make ambitions concrete, and there are governmental institutes that offer free first-line advice on environmentally friendly and nature-inclusive building principles. Find construction partners who share your ambitions. Everyone can make a difference, because choosing sustainability is not always more expensive, contrary to popular belief, but often requires more creativity, coordination, and research.

Finally, what message would you like to pass along to architects?

Architects: the societal reflex that precedes the tightening of standards, laws, and regulations lies in your hands. Be critical of projects and clients that do not prioritize societal benefits. Challenge the demand and dare to refuse when there is too much resistance. The climate is impatient – some projects may be better off not being realized. Let’s work together towards a more enriching architectural culture.

Latest insights & stories

MOBILIDATA

In Flanders, we strive to work on tomorrow’s mobility today. That includes the Mobilidata programme. With this programme, various levels of government, companies and researchers are jointly developing innovative, technological traffic solutions for road users, such as better route advice, tailored traffic notifications and intelligent traffic lights. New connected mobility and know-how do not stop at our national borders however, so international collaboration is needed to exchange knowledge and set up joint projects to implement it.

Digital sovereignty guarantees data security in the public cloud

When companies consider migrating to the public cloud, they are sometimes held back by security risks and compliance and governance constraints. Thus the interest in digital sovereignty, Gwénaëlle Hervé, Public & Sovereign Cloud Lead at Proximus NXT, explains.

ROAD SAFETY

Since 2018, the number of traffic casualties in Flanders has risen again. Currently, the figures are stagnating, but the risk of accidents with injuries remains high for vulnerable road users in Flanders. And that while traffic should be safe for all users and modes. We want to change this by focusing on transparent policy, training on safe behavior, infrastructure improvements, legislation and enforcement.